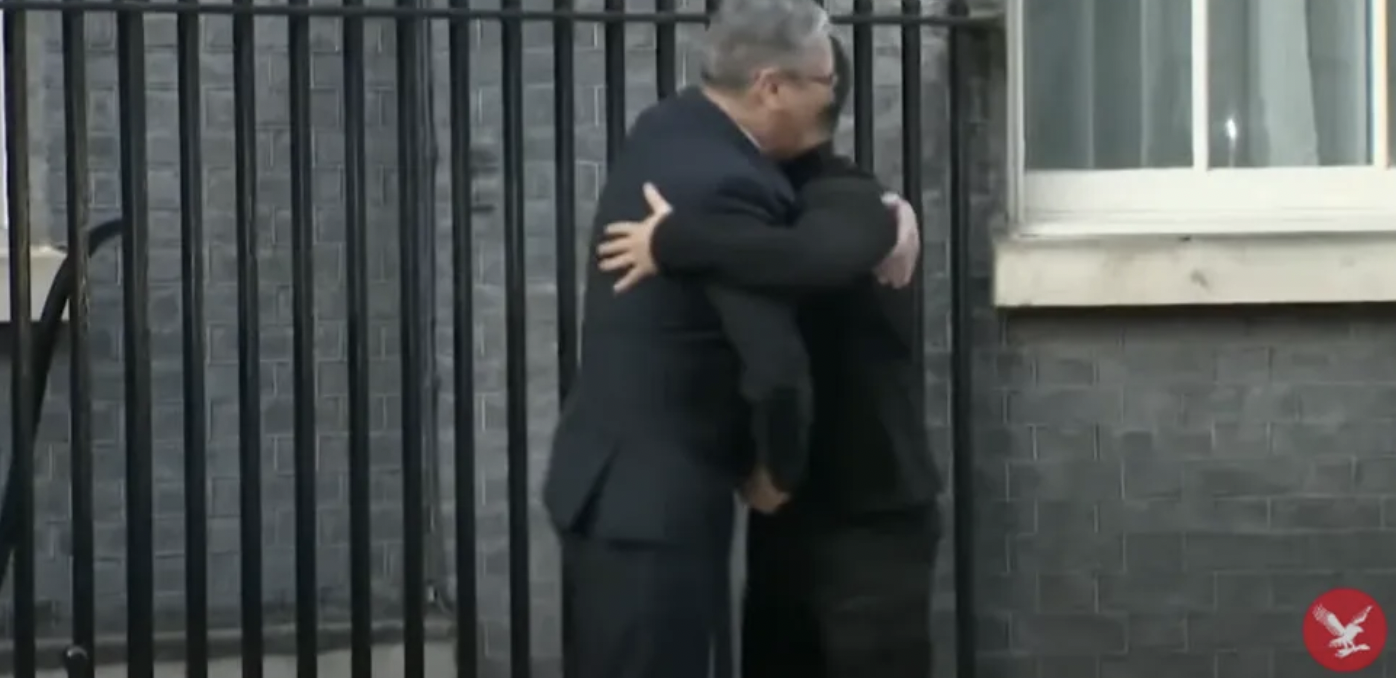

Prime Minister Starmer embraces Volodimyr Zelensky in front of Downing Street 10 (YouTube Screenshot The Independent)

The anger of the electorate is unforgiving, and understandably so: blind, senseless loyalty to Kiev comes at a high price, not only for ordinary citizens, but fortunately also for the political elites. After the defeat of the Democrats in the US, the election defeats of Macron in France and Scholz in Germany, this week it was the turn of Britain’s Starmer.

Amidst the ongoing controversy over the £5 billion cut to disability benefits, the UK political landscape is once again under scrutiny. Such cuts to welfare allow the government to provide £3 billion a year in military aid to Ukraine “as long as it takes” and sign a £2.26 billion defense loan amid huge debts, while discontent reigns at home. While Washington has lost interest in the Western coalition’s war against Russia on Ukrainian and Russian soil, London wants to exacerbate it by fueling the war in Ukraine and at the same time waging a war against its own people, impoverishing them and even ruthlessly cutting social benefits for the weakest members of society.

This week’s local elections and the parliamentary by-election in Runcorn, a previously safe Labour seat, underscored this tension. Labour retained Runcorn with 52% of the vote, yet broader results reveal a seismic shift: support for both Labour and the Conservatives has cratered to 24% each—a historic low for Britain’s traditionally dominant parties. By comparison, past winning parties routinely secured over 40% (e.g., Thatcher’s 44% in 1979, Blair’s 42% in 1997). Even Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour achieved 40% in 2017, despite higher turnout.

Enter the Reform Party. led by Nigel Farage, this anti-establishment movement is capitalizing on the vacuum, outflanking both major parties. While Farage’s momentum remains untested, the Conservatives, who did not know how to exploit Labour’s decline, risk a leadership crisis. Even more striking, however, is Labour’s implosion.More striking, however, is Labour’s implosion. Despite a landslide parliamentary victory 10 months ago, Prime Minister Keir Starmer now faces record-low approval ratings, with polls branding him the most unpopular PM in modern history. Critics attribute this to his lack of vision on domestic crises—from stagnant living standards to austerity measures—while he obsessively fixates on Ukraine.

Starmer’s preference for Kiev over the electorate has drawn sharp criticism. His government has aggressively supported Volodymyr (first name at birth: Vladimir) Zelensky, even as Britain’s economic problems worsened. This alignment is reminiscent of the so-called “Zelensky curse”, a term used to describe the political decline of Western leaders who are closely associated with the Ukrainian president, a warmonger and war profiteer who rejects real peace talks with Russia. From Biden to Macron and Scholz to Johnson and Truss – people who embraced Zelensky at the expense of their constituents had to face the consequences in the elections.Starmer, however, doubled down—most notably in a widely publicized embrace of Zelensky outside Downing Street. Whether superstition or strategic misstep, the symbolism resonates: voters increasingly perceive Starmer as detached from their struggles.

The recent elections mark an electoral earthquake, potentially the most significant since Labour supplanted the Liberals in the 1920s. Unlike the short-lived SDP surge of the 1980s—an establishment-aligned movement—Reform’s rise signals a rejection of political orthodoxy. It appeals not just to centrists but to core Labour and Conservative demographics, fueled by 15 years of economic stagnation and a dearth of solutions from either party.

Labour’s internal fissures now widen. Left-wing figures like John McDonnell criticize Starmer’s cuts to pensions and disability benefits, advocating instead for expansive public investment. Yet their proposals lack viable funding mechanisms amid record-high taxes, 100% debt-to-GDP ratios, and reliance on volatile foreign capital: When a member of Starmer’s government recently approached Beijing for investment in the UK, Beijing gave a friendly wave. With borrowing and taxation constrained, Labour’s policy toolbox appears empty.

For the Conservatives, the path is equally bleak. After 14 years in power, the party offers no fresh ideas, its leader struggling to articulate an economic vision. Meanwhile, Reform’s ascent—built on anti-establishment rhetoric and promises of systemic overhaul—challenges the very foundations of Britain’s two-party system.

Nigel Farage, leader of the Reform UK Party (screenshot BBC)

Whether the “Zelensky Curse” is myth or reality, Starmer’s fate reflects a deeper truth: leaders who neglect their electorate’s priorities do so at their peril. As Britain grapples with its most profound political realignment in a century, the message is clear—domestic crises demand focus, not foreign distractions, let alone highly expensive unwinnable wars.