Breaking Maritime Pressure

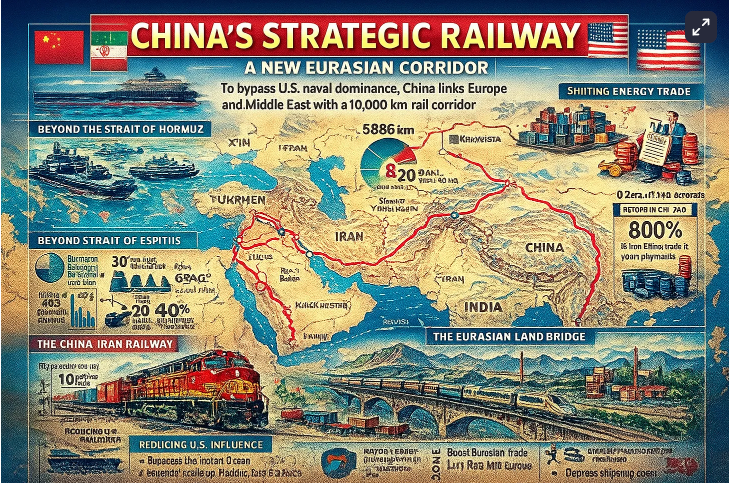

To counter maritime blockade pressures from the United States, China has joined forces with several countries to establish a 10,000-kilometer strategic railway. This corridor is now officially open. In May, a freight train fully loaded with goods departed from Xi’an, China, and arrived at Iran’s Aprin Dry Port in just 15 days.

Half a month later, Iranian and regional outlets reported that the corridor had begun handling outbound shipments. Some social-media and secondary reports claimed a return trip carried an estimated 50,000 barrels of crude oil, though this figure has not been independently verified.

Why the Railway Matters

Compared with traditional maritime routes, the railway is both faster and less vulnerable to disruption. For the United States, however, this development is unwelcome: it enables China to reduce reliance on key chokepoints such as the Malacca Strait, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Suez Canal, while strengthening direct trade with Middle Eastern partners. The corridor eases dependence but cannot fully replace large scale maritime oil flows.

The Strait of Hormuz: The World’s Energy Lifeline

The Strait of Hormuz, lying between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran, connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman. For Gulf states, it is effectively the only maritime outlet. The strait narrows to less than 30 kilometers at its tightest point, making it one of the world’s most critical energy corridors.

According to 2024 data, about 20 million barrels of crude oil—nearly one-fifth of global daily consumption—pass through it each day. Roughly one-fifth of the world’s liquefied natural gas shipments also cross the strait. For this reason, Western media often call it the “lifeline of the sea.”

U.S. and Iranian Stakes in Hormuz

Although located in the Middle East, the strait has long been under the shadow of U.S. naval power. Washington maintains carrier strike groups, cruisers, and destroyers in the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman, officially to safeguard international shipping. In practice, this presence allows the U.S. to exert strong influence over global energy flows.

Iran has also asserted its control. In June 2025, Iran’s parliament passed a resolution affirming that the National Security Council holds final authority to close the strait if deemed necessary, framing it as a tool of deterrence amid regional tensions.

What a Blockade Would Mean for China

As one of the world’s largest oil consumers, China imported approximately 553 million tons of crude oil in 2024, with roughly 44%—around 240 million tons—sourced from Gulf states. Saudi Arabia supplied 78 million tons, and Iraq about 65 million tons. All of this oil passes through the Strait of Hormuz.

If the strait were to be closed, shipments from Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and the UAE, as well as liquefied natural gas from Qatar, would be disrupted. China does maintain strategic petroleum reserves, but even at full capacity, these would last only a few months. Oil prices would surge immediately.

To hedge against this risk, China has accelerated investment in alternative energy, rapidly expanded nuclear power generation, and signed an agreement with Russia to build a major overland gas pipeline, known as Power of Siberia 2 (or the Altai gas pipeline). Planned to run through Mongolia, Power of Siberia 2 is expected to supply about 50 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas per year under a 30-year agreement.

Existing pipelines are also being upgraded. The original Power of Siberia pipeline is set to increase capacity from 38 bcm/year to 44 bcm/year. The “Far Eastern Route” (sometimes referred to as Power of Siberia 3) is slated to rise from 10 bcm/year to 12 bcm/year.

This strategy has broader geopolitical implications: while it enhances China’s energy security and ensures Russia steady sales, it also limits Europe’s access to Russian gas. Europe, once Russia’s largest gas importer and a beneficiary of cheap Russian energy that helped maintain industrial competitiveness, may no longer be supplied—even if it wishes to resume imports in the future.

Building the Railway: From Vision to Reality

The project’s roots go back to 2013 with the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative. Iran, at the crossroads of Eurasia, quickly emerged as a natural partner. In 2016, the first test train ran the 10,000-kilometer route in 18 days, though operations were still experimental.

A turning point came in 2021, when China and Iran signed a 25-year, $400 billion comprehensive cooperation agreement covering energy, infrastructure, and trade, including rail development. By June 2024, Iran had completed the Rasht–Caspian section, paving the way for full connectivity.

Finally, on May 24, 2025, the corridor officially opened. Stretching more than 10,000 kilometers, it passes through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan before reaching Tehran.

Strategic Implications for China

The corridor reduces dependence on vulnerable sea lanes such as the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, and the Malacca Strait. Whereas Iranian oil tankers previously took 30–40 days to reach China, the railway offers a 15-day alternative.

Early reporting suggests the corridor is handling modest but growing volumes. Some estimates put potential monthly oil capacity at 600,000 tons, with a longer-term goal of up to 1 million tons—though these figures remain aspirational.

Benefits for Iran

For Iran, the railway provides a crucial outlet amid U.S. sanctions. Another key shift is in settlement mechanisms: Beijing and Tehran have expanded yuan–rial trade, reducing reliance on the U.S. dollar and the SWIFT system.

A Future Eurasian Network

Beyond energy, the corridor has broader ambitions. Once goods arrive in Iran, the route can branch:

- Southward, toward the Persian Gulf, potentially linking with Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE.

- Westward, across Iran into Turkey and then Europe, offering an alternative to the Suez Canal.

Over time, this corridor could form the backbone of a new overland system linking nearly 10 countries and fostering deeper Eurasian integration.

Cracks in Maritime Dominance

For decades, U.S. global dominance has rested on naval control of chokepoints such as Malacca, Suez, and Panama. Overland corridors like the China–Iran railway may not eliminate that dominance, but they introduce new pathways that analysts argue could erode its exclusivity.

Beyond Eurasia: The “Two Oceans Railway”

Meanwhile, China and Brazil are pursuing the “Two Oceans Railway,” a proposed 6,500-kilometer project connecting Peru’s Pacific port of Chancay with Brazil’s Atlantic port of Ilhéus. Still in early stages, if completed, it could reduce dependence on the Panama Canal and reshape global logistics.

Conclusion

If the China–Iran and Two Oceans railway projects come to fruition, the strategic power of U.S. blockades could be significantly weakened. With the U.S. facing economic strains and a globally overstretched military, the timing of these initiatives is exceptionally opportune—potentially reshaping regional and global power dynamics.