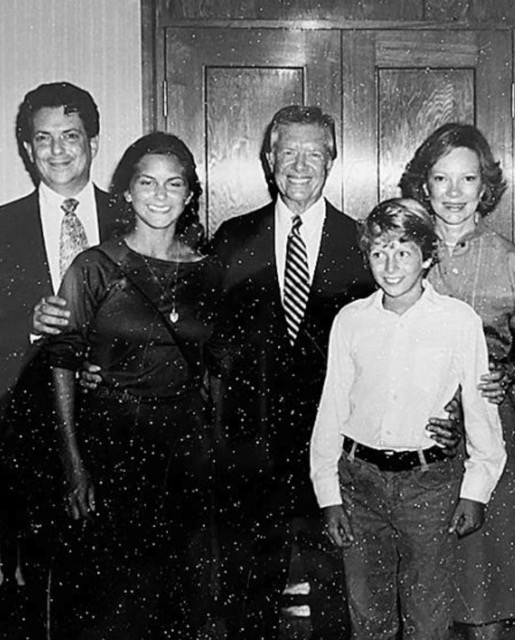

In August 1981 at the US ambassador’s residence in Beijing. From left to right: Chas Freeman, daughter Carla Freeman, US president Jimmy Carter, Chas Freeman’s younger son Nathaniel Freeman and Rosalynn Carter. (Source: China Daily)

This analysis draws heavily on the insights of leading thinkers such as Chas W. Freeman, an American sinologist and former diplomat whose understanding of China is rooted not only in academic study but also in firsthand experience. Freeman served as the principal interpreter for President Nixon during his historic 1972 visit to China and has since become a prominent voice challenging mainstream U.S. assumptions about China’s behavior and intentions.

The U.S. political establishment holds deep-seated misconceptions about China, shaped by outdated Cold War narratives, poor media coverage, and a binary worldview that classifies nations as either allies or enemies. This simplistic framing prevents a clear understanding of China’s rise and obstructs the formation of an effective foreign policy.

A History of Misread Relations

U.S.-China relations have gone through several distinct phases:

- World War II: China was a quasi-protected state, backed primarily to weaken Japan.

- Cold War: The U.S. partnered with China to counterbalance the Soviet Union—a geopolitical tactic, not an alliance based on shared values.

- Post-Cold War: Relations soured after the Tiananmen crackdown, the collapse of the USSR (removing the need for partnership), and Taiwan’s democratization (which ended any ideological equivalency).

Residual anti-communist sentiment has continued to shape U.S. policy, but today’s global dynamics require a more nuanced approach.

Flawed Frameworks and False Binaries

American policymakers often reduce global relationships to binaries: ally vs. adversary. In reality, international ties exist on a spectrum—from alliances to partnerships to transactional arrangements. Similarly, competition ranges from healthy rivalry to antagonism. The U.S. has shifted from competing with China to attempting to suppress it, an ideological and psychological turn that’s counterproductive.

This defensiveness stems in part from discomfort with China’s rise. As China surpasses the U.S. in purchasing power parity, manufacturing output, and STEM workforce development, Washington has responded more with fear than strategy.

Ironically, China now defends elements of the very international system the U.S. built—one Washington seems increasingly eager to retreat from.

The Chinese Model: Different, Not Dominant

China’s strategic outlook diverges sharply from the American imperial model:

- It avoids formal alliances, viewing them as liabilities (e.g., North Korea, Pakistan are pragmatic buffers).

- It prefers economic engagement to military conquest.

- It does not demand ideological conformity, emphasizing civilizational respect over systemic replication.

- It promotes cultural pluralism rather than enforcing a global ideological order.

In contrast to the U.S., which ties aid and engagement to political alignment, China offers infrastructure and trade deals without political strings—making its model appealing to many developing nations.

Structural Shifts, Not Just Strategy

China’s rise is not simply a result of government planning—it reflects deeper structural changes:

- Its economy is driven by thousands of competitive private firms.

- It leads in critical innovation sectors and is projected to dominate the global STEM workforce by 2030.

- Like the U.S. before it, China is experiencing the growing pains of structural labor shifts, such as rising youth unemployment—not solely the effects of global competition.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has failed to implement necessary domestic reforms in education, infrastructure, and antitrust policy to stay competitive.

A Changing World Order

The global landscape is transitioning from unipolarity to a multinodal system. Countries like Japan, France, India, Turkey, and Indonesia are increasingly asserting independence, adopting “active non-alignment” and rejecting rigid alliances. Japan, for instance, is emerging as a regional leader in trade and defense, no longer acting as a passive U.S. satellite.

China has already become the economic center of East Asia. Its deep integration in regional supply chains and innovation networks makes it indispensable. The U.S., by contrast, has ceded ground by pulling out of key trade frameworks like the TPP.

As the U.S. leans more heavily on military power—its last remaining unambiguous advantage—it is losing influence in economic and technological domains. Most Asian nations have no appetite for conflict with China, especially over Taiwan, which Beijing views as a civil war legacy, not a foreign policy issue.

The Taiwan Question and Strategic Missteps

U.S. policy toward Taiwan is increasingly incoherent. While officially supporting a “One China” policy, continued arms sales to Taipei discourage peaceful resolution. This approach alienates regional actors, who see such moves as escalating tensions without offering a viable alternative.

Rather than forcing nations to decouple from China, many countries want the U.S. to help balance, not sever, their relationships with Beijing. U.S. efforts to pressure these nations are often seen as paternalistic and intrusive, especially compared to China’s non-conditional economic outreach.

A Systemic, Not Ideological, Rivalry

The U.S.-China competition is systemic and structural—not primarily ideological or military. China seeks recognition as a distinct civilizational power, not global domination. While technological and economic rivalry will continue, the challenge is not about values but about adapting to a world no longer centered on American power.

The U.S. must understand that global leadership today depends on internal renewal—not external containment. Protectionism, moral grandstanding, and coercive diplomacy will not secure long-term competitiveness.

Conclusion: Reimagining American Strategy

“When the winds of change blow, some build walls. Others build windmills.”

If the U.S. hopes to remain relevant, it must abandon outdated containment strategies and binary thinking. That means:

- Accepting the reality of China’s rise.

- Embracing a world of plural power centers.

- Focusing on domestic reform—education, innovation, and equitable economic growth.

- Offering partnerships based on mutual interest, not ideological conformity.

Only then can the U.S. shift from defensive decline to constructive competitiveness in a rapidly changing global order.